A Chilean Bryologist Visits the UBC Herbarium

By Saskia Wolsak

Today, we celebrate the launch of Enciclopedia de la Flora Chilena, an online encyclopaedia of Chile’s diverse plant population that visiting Chilean bryologist Felipe Osorio has worked on for two years. Similar to British Columbia’s E-flora BC, the website provides photos and descriptions of thousands of plant species, all with available distribution, bibliographical, and taxonomic information.

The UBC Herbarium welcomed Osorio to spend a week with us, studying mosses common to both Chile and Canada. He analysed specimens, squinted into microscopes, read books from the herbarium library, and took detailed photographs. The information Osorio gathered will help to complete the species descriptions of the more than 500 mosses to be added to the website by November.

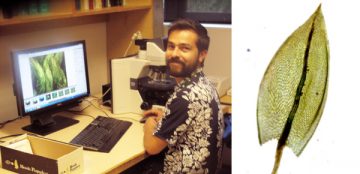

Chile is home to over 1,400 species of bryophytes (mosses, liverworts and hornworts), including representatives of 10% of the world’s species of mosses with many endemic species, that is, species that grow nowhere else in the world. Among these mosses are one of the world’s tallest mosses, Dendroligotrichum dendroides; a moss with clear leaves, Acrophyllum magellanicum; and one that hangs like netting, Weymouthia cochlearifolia, coating the lush rainforests of southern Chile.

With such great diversity and so much at stake, it is surprising that Chile has so few bryologists – “Fewer,” says Osorio, “than you can count on one hand.”

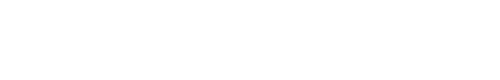

(Left) Felipe Osorio in the herbarium office. Photo: Saskia Wolsak (Right) Bryum alpinum, taken by Felipe Osorio at the UBC Herbarium.

Osorio and the team at Flora Chilena don’t want researchers to have to start from scratch. “There is so little information available about the mosses of Chile,” says Osorio. “Our goal is to collect it here and share knowledge of the distribution, description, taxonomy, resources, and photos of each species; then anyone can access it, see what has already been done, and begin from there.”

I interviewed Osorio in the niche café at the Beaty Biodiversity Museum. We had just a few minutes left so I asked a final question, “Why study mosses at all?” Osorio hesitated.

“For me the purpose is purely romantic. I… I just love them. I love the mosses. They are the only organisms that really challenge me. They are so difficult to identify. You can identify vascular plants simply by looking at their colour and their leaves, for example, but bryophytes you need a microscope – they are a constant challenge.”

(Left to right) Acrophyllum magellanicum and Weymouthia cochlearifolia. Photos: Felipe Osorio

“And the greater purpose?” I asked. “Why should other people be interested?”

“In Chile there is such constant anthropic pressure on the ecosystems; unless we study them and try to learn as much as we can, they will disappear without us knowing anything about these beautiful plants.” I was taking notes as fast as I could, and thought I may have misheard him.

“Did you say ‘beautiful’ plants?”

“Yes,” he beamed, “beautiful plants!”

The Chilean Flora Chilena website, with 5,000 of the approximately 5,200 vascular plants of Chile and almost 50% of the mosses, celebrates its official launch on August 2, 2013.

Osorio could not leave without expressing his gratitude to everyone at the UBC Herbarium, especially Olivia Lee, Judith Harpel, and Steve Joya for providing the space, information, and personal introduction to the forest and mosses of Vancouver.

(Photo at the top) Dendroligotrichum dendroides and a fellow researcher holding a Dendroligotrichum dendroides, which can grow up to 40 cm long. Photos: Felipe Osorio