The Beaty Biodiversity Museum’s 2.1 million specimens are much more than just fascinating objects on display – they are critical aspects of contemporary research. For example, historical samples of threespine sticklebacks (a freshwater fish) housed in the museum were used to document the extinction of British Columbia’s unique “benthic” and “limnetic” sticklebacks in Enos Lake on southwestern Vancouver Island – a story that reached the New York Times.

Glaucous-winged gull chick. Photo by Louise Blight.

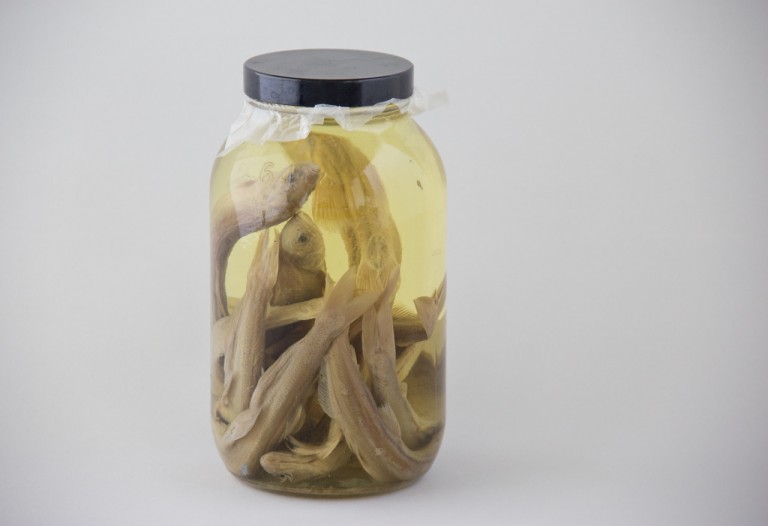

More recently, and in an article in Global Change Biology, Louise Blight and colleagues used historical collections of bird feathers from the museum’s Cowan Tetrapod Collection and muscle from marine fishes in the fish collection to examine changes in the diet of glaucous-winged gulls (Larus glaucescens) in the Salish Sea. The feathers and muscle, collected between 1860 and 2009, were examined using stable isotope analysis, a technique that exploits the fact that animal tissue has an “isotopic signature” (typically expressed in the ratios of certain forms, or isotopes, of carbon and nitrogen). This signature is determined, in large part, by what the animal eats; the historical gulls’ feathers showed stable isotope values representative of marine, mid-trophic signatures expected from a diet high in forage fishes like eulachon (Thaleichthys pacificus) and Pacific sand lance (Ammodytes hexapterus) (and from published observations we know that these birds fed more extensively on these fishes in the past). What Blight and colleagues showed was that the diets of the gulls had changed dramatically across the 150 year time period; the gulls’ diet became less characterized by marine foods and more characterized by food items of lower trophic levels.

Adult glaucous-winged gull. Photo by Louise Blight.

These results strongly suggested that the gulls were now feeding less frequently on marine fishes and likely more on invertebrates and terrestrial sources of food (e.g., perhaps human-generated garbage). The shifts in the gulls’ diet may have been driven by observed concurrent declines in the abundance of forage fishes such as eulachon, Pacific herring (Clupea pallasii), pilchards (Sardinops sagax), and capelin (Mallotus villosus), all of which are nutritionally of high value. Blight and colleagues also point out that the trend towards a lower quality diet of glaucous-winged gulls is associated with a decline in their reproductive output and abundance.

Eulachon. Photo by Beaty Biodiversity Museum.

These examples of the use of museum collections illustrate the “added value” that such collections, made long ago and typically well before many techniques used in contemporary research were developed, contribute to biodiversity research and conservation efforts. In a similar vein, these examples illustrate that biological collections made long ago (or today) may have tremendous utility in ways that could not be imagined when those collections were first made.

For more information see: Blight, L.K., Hobson, K.A., Kyser, T.K. and Arcese, P., 2015. Changing gull diet in a changing world: A 150‐year stable isotope (δ13C, δ15N) record from feathers collected in the Pacific Northwest of North America. Global Change Biology 21:1497-1507.