Two new fossils of the dragonfly order of insects have been discovered near Princeton. One is a darner, a dragonfly family still common today. It would not look out of place flying beside a pond in British Columbia right now. The other is an extinct dragonfly relative that would be a tremendous shock to see in the modern world.

Descriptions and names of the fossils were recently published in the scientific journal The Canadian Entomologist by paleontologist Bruce Archibald of the Beaty Biodiversity Museum of the University of British Columbia and Robert Cannings, emeritus entomologist with the Royal British Columbia Museum.

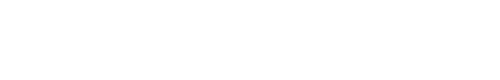

The wing of the new species of dragonfly relative Allenbya holmesae, found by Beverly Burlingame of Princeton, BC

Fossil insects have been collected in the Princeton region by scientists for 150 years, but never one of the dragonfly order until now. George Mercer Dawson of the Geological Survey of Canada first reported fossil insects in British Columbia in 1877. He found them near Princeton on the banks of the Similkameen River. As there were no fossil insect experts in Canada in those days, these specimens found their way to Samuel Scudder of Harvard University and Anton Handlirsch at the Natural History Museum in Vienna, who described them in scientific publications.

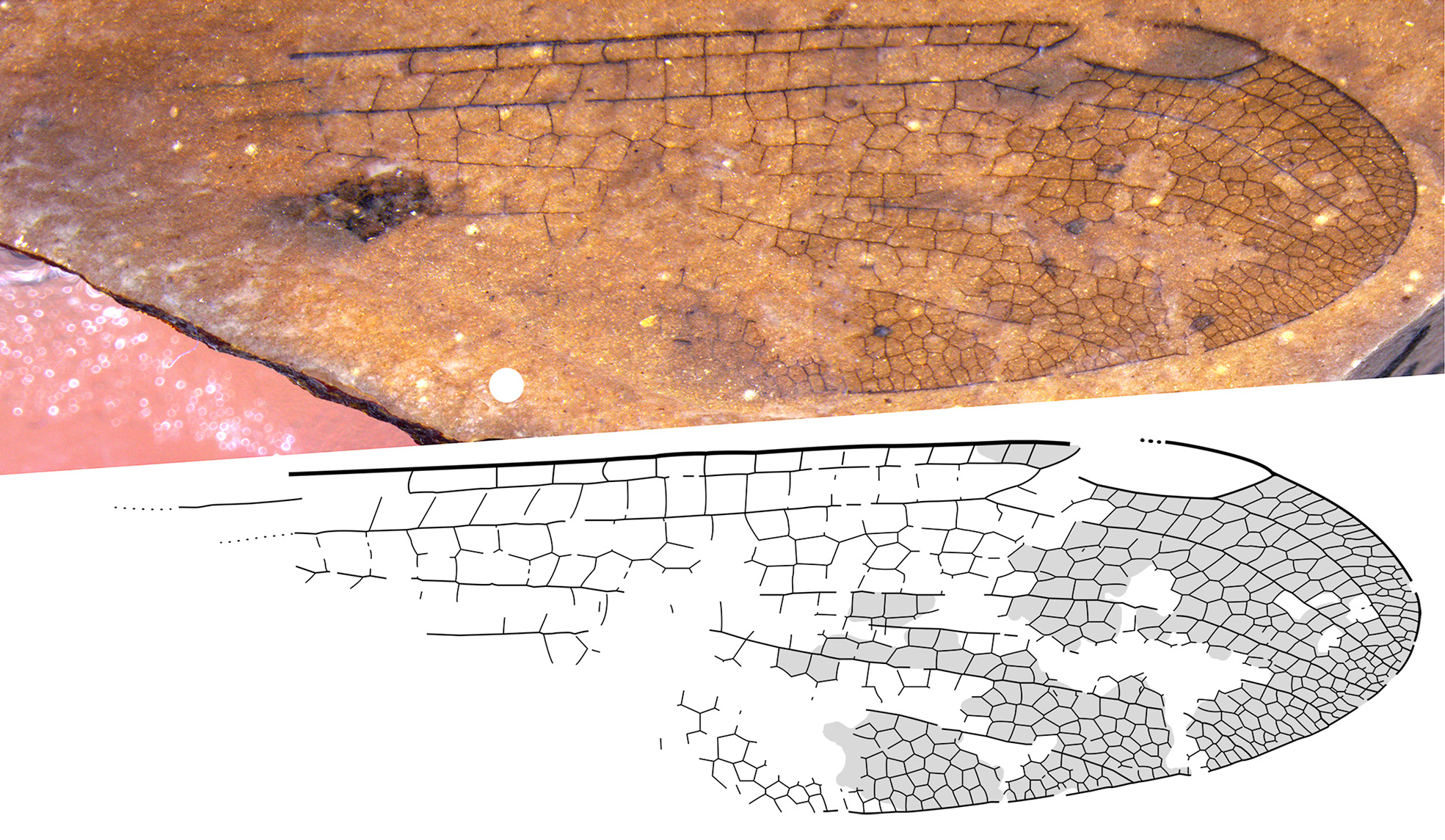

From left to right:

- George Mercer Dawson of the Geological Survey of Canada first found fossils near Princeton, BC in 1877.

- Samuel Scudder of Harvard described fossil insects in the late 19th Century that George Mercer Dawson had found near Princeton, BC soon after the province entered confederation.

- In 1910, Anton Handlirsch in Vienna wrote about fossils found along the Similkameen River near Princeton, BC.

Several other paleontologists collected on the banks of the Similkameen over the next century and a half. They wrote about the rich record of many kinds of fossil insects from these beds, but never one of the dragonfly order.

That all changed through the efforts of Princeton residents Kathy Simpkins, manager of fossil collections at the Princeton Museum, and Beverly Burlingame, an avid collector who regularly brings fossils to the museum.

When Archibald visited the Princeton Museum in 2021, Simpkins showed him a fossil of a torn and folded part of a wing that she’d found. “The wing was so messed up I had no idea what kind of insect it belonged to,” she said. By its preserved intricate net-like venation, however, Archibald recognized it as part of a dragonfly wing.

“I was excited to see this specimen because no dragonfly had ever been found in this geological formation before”, Archibald said. At the time, he was working with Robert Cannings on some other fossil insects of the region, and they quickly decided that they needed to publish a description of the wing.

They knew that it belonged to the darner family, but the insect remains were too incomplete to tell what species it might be. Still, “knowing that darners flew in the Princeton region about fifty million years ago is an advance in our knowledge” noted Cannings, adding “they are diverse in BC today, and now we know that they were doing well here way back then.”

A few months later, Beverly Burlingame texted Archibald an image of another insect wing fossil. It turned out to be a member of an extinct relative of dragonflies and damselflies that Archibald and Cannings had named the “Cephalozygoptera” earlier that year. This insect would certainly look strangely weird flying along the shores of a modern pond, lake, or stream.

They named this new species Allenbya holmesae. Allenbya refers to the geological formation where the fossil was discovered and holmesae recognizes Burlingame’s mother, Dorothy Holmes, who worked with entomologists at Agriculture Canada for many years and instilled a love of insects and fossils in Beverly in her youth.

What’s next? “Kathy and Bev have found a series of important fossils, and these will be published over the next few years. It’s amazing what they come up with,” said Archibald. Their fossil finds are wonderful examples of the contributions that naturalists and keen amateurs can make to our understanding of biology.

Simpkins and Burlingame will be splitting more rock in search of ancient life. Burlingame says: “finding these fossils is exciting, and learning their significance to science is incredible!” So, watch for more.

Kathy Simpkins (left) and Beverly Burlingame (right) of Princeton, BC are finding fossils important to science in the Princeton region in the tradition of George Mercer Dawson a century and a half later.

A free PDF of the scientific paper “The first Odonata from the early Eocene Allenby Formation of the Okanagan Highlands, British Columbia, Canada (Anisoptera, Aeshnidae and cf. Cephalozygoptera, Dysagrionidae)” can be downloaded at brucearchibald.com.

Read the CastaNet article.

Listen to the CBC Kelowna interview:

CBC – Daybreak South with Chris Walker

In French, Radio Canada.

Contact:

Dr. Bruce Archibald, phone (778) 840-6260, email: bruce.archibald@ubc.ca

Dr. Robert Cannings, email: RCannings@royalbcmuseum.bc.ca

Princeton Museum Manager Todd Davidson, phone (250) 295-7588, email: princetonmuseum@gmail.com

Princeton Museum Director Marjorie Holland, email: holland.marjorie@gmail.com