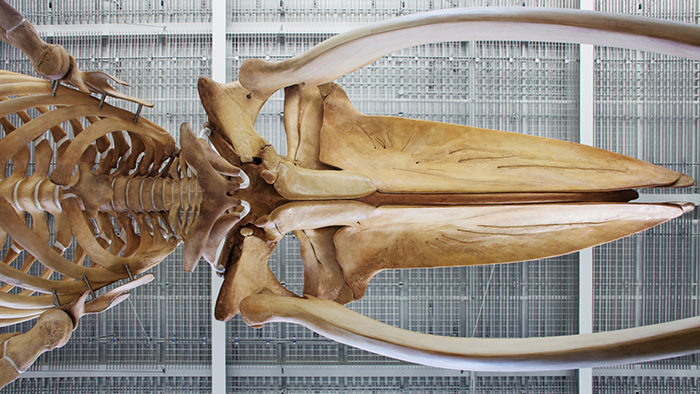

Step inside the museum and it’s hard to miss the blue whale skeleton in the atrium – one of few places in the world where you can get close to the largest creature that has ever lived on Earth!

Big Blue’s journey to the museum was not straightforward. Moving the skeleton from the coast of Prince Edward Island to the UBC campus 6000 km away, was a challenging project. You can watch a documentary about raising Big Blue when you visit the museum – check our daily schedule for up to date screening times. Check out our step-by-step guide to drawing the Beaty Biodiversity Museum’s largest specimen!

Blue whales rarely strand on beaches, and very few skeletons have been recovered for research or display. Worldwide, only 21 are available to the public for viewing.

The Beaty Biodiversity Museum is home to Canada’s largest blue whale skeleton, a magnificent specimen that illustrates the interconnectedness of all living things.

Blue Whale Burial: 1987

On the remote northwestern coast of PEI in 1987, a 26 m long mature female blue whale died and washed ashore near the town of Tignish.

In hopes of preserving the whale’s skeleton for research or museum display, the PEI government and the Canadian Museum of Nature arranged for the skeleton to be dragged off the beach near Nail Pond, and buried. The remains of the whale were longer than two Vancouver trolley buses parked one behind the other, and weighed an estimated 80,000 kg. Her burial was a mammoth task.

Exploratory Expedition: December 2007

In mid-December, the Museum sent a team of four to PEI to investigate the condition of the blue whale skeleton buried at Nail Pond, and determine if recovery was possible. They planned to find the whale carcass, excavate the burial site, and remove a few bones, to check their condition.

Recovery Expedition: May 2008

In May, an expanded team of UBC researchers and affiliates headed to PEI to retrieve the entire blue whale skeleton. First, a trench alongside the whale was dug with an excavator. Using shovels, pickaxes, and other tools, the team exposed the carcass and peeled away the remaining skin, flesh, and blubber. The bones were removed, cleaned, labeled, and packed in a refrigerated container from CN rail.

Degreasing: July 2008 to November 2009

Whale bones are extremely porous. Up close, some areas look like giant sponges. The whale bones are filled with oil in living animals, which helps with buoyancy. Over the 20 years the whale was in the ground, this oil had gone rancid and smelled terrible. The oil would need to be removed before the whale could be put on public display. The removal of this oil was the degreasing phase of the project.

Mike deRoos, the Blue Whale Project’s Master Articulator, and his team removed the whale bones from the cargo container that brought them across the country. The bones were moved to large, specially-designed degreasing tanks built in a space generously donated by Ellice Recycle Ltd. on Victoria’s inner harbour. The team sprayed the bones with degreasing enzyme, a biological agent that helped to break down the oil molecules. The bones were then immersed in 2,500 gallons of liquid containing a type of bacteria that could further digest the oil. This procedure removed the majority of the whale oil from the bones over a period of several months.

In November 2008 team of UBC microbiologists, joined by a camera crew from the Discovery Channel, visited the degreasing site to asses the state of the solution in which the whale bones were soaking. The UBC contingent consisted of Gary Lesnicki, from the Michael Smith Labs, and Doug Kilburn and Tony Warren, retired UBC professors. As part of their recommendations, the temperature of the solution was raised, and the rate of extraction of the oil increased dramatically. Later in the next year, some of the larger blue whale bones underwent a vapour degreasing process.

This procedure extracted remaining traces of oil from deep within the bones by exposing them to a vaporized degreasing enzyme. The jawbone was so big, it had to have a custom tank built for it.

Articulation: January to April 2010

As the bones made their way out of the enzyme baths, the workshop became a much more interesting (and less smelly) place. The articulation phase involved bone repair and casting, and putting all of the pieces together. Mike deRoos, our master skeleton articulator, roughly arranged the first bones out of the bath to get an idea of how to piece the skeleton together.

As the workshop got into gear, the team were happy to welcome field trips from schools and educational organizations, as well as the general public during several open houses. In June of 2009, a class of Grade One students from Frank Hobbs Elementary visited the Blue Whale Project Workshop.

Installation: April to May 2010

The Blue Whale project team completed articulation at the beginning of April 2010. The whale’s massive skeleton was packed up and safely taken for her final voyage at sea with the help of VanKam Transport and BC Ferries. She arrived at UBC on April 7, 2010, almost exactly two years after she was exhumed in PEI.

The team began the installation on a good note, managing to squeeze the nine large articulated sections of the skeleton (four sections of vertebrae, the skull, two jawbones and two flippers) into the atrium without an inch to spare. Before they began suspending the skeleton, all the pieces were scanned by NYX Dimensions to create a digital copy of the entire skeleton. This information is unique and will be valuable for research and interpretation.

Sections were lowered to a staging area in the lower level of the atrium. The team then hoisted the sections to their final positions working from skull and jawbones back toward the tail. Once in place, permanent stainless steel cables were installed from custom fabricated attachment points in the skeleton to pre-installed u-bolts in the ceiling of the atrium. Even though the team had tirelessly worked with the bones every day for almost two years, this was the first time anyone on the team had seen the skeleton in her entirety since PEI.

The talented crew of articulators, painters and sculptors joined us to complete the finishing touches on the skeleton and she was ready for the crowds who attended a great first blue whale preview event on May 22, 2010. The completion of this blue whale skeleton was a truly collaborative accomplishment for everyone involved from coast to coast and the team and Museum are thankful to all of the amazing supporters, donors and volunteers who made it a reality.

Exhibition: May 2010 to Present…

The whale skeleton is on permanent display at The Beaty Biodiversity Museum. At 26 m long, it is the largest blue whale skeleton on display in Canada, and one of only 21 worldwide.

The Team

A vast number of people have come together to make this project possible. We are deeply appreciative of everyone who has contributed time, energy, and talent to this massive undertaking.

Dr. Andrew Trites and fellow researcher Claudia Hernandez.

Dr. Andrew Trites

Dr. Andrew Trites is an Associate Professor and Director of the Marine Mammal Research Unit in the Fisheries Centre at the University of British Columbia, and is the Research Director for the North Pacific Universities Marine Mammal Research Consortium. He has served as a member of the US Steller Sea Lion Recovery Team, the Canadian Killer Whale Recovery Team, a voting member of the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC), and co-chair of the Marine Mammal Specialist Group for COSEWIC.

Furthering the conservation and understanding of marine mammals, and resolving conflicts between people and marine mammals are central to Dr. Trites’ research. His research involves captive studies, field studies and simulation models that range from single species to whole ecosystems.

Mike deRoos, Skeleton Articulator

Mike deRoos is the master skeleton articulator on the project. A native of Vancouver, he has always been interested in biology, the ocean, and building things large and small. During his BSc (completed in part at UBC), he articulated his first marine mammal skeleton (a sea otter) as part of a field course at the Bamfield Marine Station. The project combined his interest in marine biology with construction experience gained working in the family contracting business. He proved a natural at this unconventional line of work, and started his own independent contracting business in 2004. Since 2000, Mike has articulated eleven marine mammal skeletons, including an 18 m fin whale on display at the Johnstone Strait Killer Whale Interpretive Center, and a killer whale, minke whale, three pacific white-sided dolphins and two Steller sea lions on display in the Aquatic Ecosystems Research Labs building at UBC. Photos of these projects and Mike’s other work can be seen on cetacea.ca

Thanks also to…

|

Michiru Main Jesse McBeath George Hudson Bob deRoos David Hunwick Elizabeth Thomson |

Kim Woolcock Leah Thorpe Natalie Bowes Joanne Thomson Frank Hadfield Gilles Danis Ken Kucher and our many volunteers |

|

Acklands Grainger Incorporated Artworld Picture Framing and Art Supplies British Columbia Ferry Services Incorporated Canadian Museum of Nature Canadian National Railway Company Ellice Recycle Limited Emery EH Electric Limited Fairey & Company Limited McLean Foundation Novozymes North America Incorporated Nyx Dimensions Prince Edward Island Veterinary College |

Province of Prince Edward Island Rekord Marine Enterprises Limited Reliance Specialty Products Incorporated Royal Ontario Museum Sherwood Motor Inn UBC Bookstore Univar Canada Limited Van Kam Freightways Limited Viking Air Limited Walkers Saw Shop WestJet Airlines Limited |