My mother tells me that when I was four years old, I went for a walk with the daycare staff one day and ate a mushroom. I picked it up and popped it into my mouth before any of the adults realized what I was doing. They rushed me to the hospital to pump my stomach, just in case, but apparently I was perfectly fine. 17 years later, I look around for a directed studies project and “Would you like to go out and collect mushrooms?” Mom tells me she is not surprised. After all this time, I’m still curious.

I was lucky when I was younger, but that is not always the case. About 6,000 cases of mushroom poisoning were reported in the US in 2010 (Alvin et al. 2011). While this is certainly not a large amount relative to the number of people collecting and consuming mushrooms, mushroom poisonings are a problem in healthcare. Some are child accidents like mine; some are looking for “magic” psychotropic mushrooms. Others are natural food enthusiasts turned mushroom foraging fans, often relying on misleading or contradictory guidebooks, who easily confuse edible and toxic species. Frequently immigrants from places where mushroom hunting is a common pastime, such as Russia, may be unfamiliar with local species and mistake them for similar edible species from home. Whatever the motivation, there is a growing body of mushroom pickers with incomplete facts about North American-specific species.

There are over 2,300 species of mushrooms used worldwide as food and medicine (Boa 2004). Important economically, Canadian mushroom culture and harvest industry earned an excess of 30 million in 2003 (Boa 2004). Wild mushroom harvesting also serves as a much needed source of protein and amino acids for rural people in developing countries. Mushroom use varies depending on cultural acceptance. Historically North Americans have been more wary than others, and there is also a shorter tradition of mushroom collecting than in Europe. Species descriptions are often European, and may not match variants endemic to North America which have yet to be defined. This means that mistakes are more easily made; better identification of local macro-fungi would benefit public health. As a directed studies student with Dr. Berbee’s lab at UBC, I set out to contribute by collecting both edible and poisonous mushrooms in our area and including them in the UBC Herbarium. Distribution and morphology information about local species, as well as samples of tissue for DNA analysis, could be useful to future researchers and mushroom pickers alike. In addition, creating a list of local toxic species means there is a better chance of identifying the species responsible in a poisoning case and providing effective treatment. Ideally this database could help prevent future poisonings as well as collect data about the diversity of local fungi.

Before I knew it I was off on a mushroom foray at Manning Park with the Vancouver Mycological Society. A bewildering array of shapes and smells and scientific names greeted me; and I was delighted to find mushrooms that are not the common white or brown but shocking shades of pink, blue, orange, and green. The experienced enthusiasts were not only collecting delicious edibles, they were generating local data by creating a list of every species they found. Inspired, I returned home with many promising samples—but this was just the beginning. Throughout September and October I went on several more collection trips around campus and beyond. Walking down Main Mall in November, I was surprised to find that Amanita muscaria sprouts ostentatiously on our UBC campus. This is the famous “Mario mushroom” with distinctive red cap and white warts.

A group of A. muscaria fruiting at the base of an oak. Photo by Sarah Ellis.

- muscaria, like many mushrooms, is in a symbiotic relationship with surrounding trees and is vital to the trees’ health. The “mushroom” part is like a flower grown to spread seeds; the actual main body of the fungus is below ground in a mycelial mass that exchanges nutrients with the tree roots year-round. Besides its important ecological roles as a decomposer, symbiont, and food source, A. muscaria has had thousands of years of history with us. People have found a multitude of uses for the “fly agaric”, from decorating Christmas trees in Germany to using its poisons to kill flies in the home (Marley 2010). It is perhaps most famous as a visionary hallucinogenic. Even reindeer are attracted to the effects which turn the normally docile creatures “frisky”; they will actively seek it out, including the urine of people that have eaten it (Marley 2010). However, A. muscaria contains ibotenic acid and muscimol, which may induce psychedelic effects but are primarily poisonous. They cause symptoms ranging from nausea and muscle spasms to a deep coma-like sleep with intense visions, proving fatal in 5% or more of cases (Marciniak 2010). Both an integral part of the ecosystem and a deadly poison, A. muscaria is an example of the complexity of mushrooms and the conflicting definitions of “edible” mushrooms.

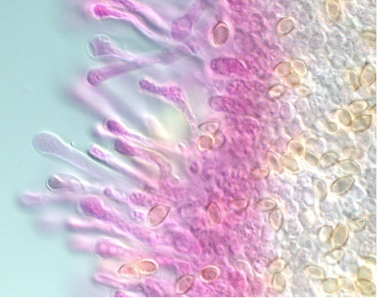

Unfortunately, most of my other mushroom specimens weren’t so easily recognizable. I went to the lab to wrestle with identifying what mushrooms I had found. Most of the available literature describes European species, so it is harder than you might think to figure it out. Often a species description will not quite match, or it is hard to find a likely species because the dichotomous keys rely on information, such as smell, that I hadn’t observed. I began to appreciate what kinds of characteristics were used to differentiate species… and I quickly found out just how bad my collection notes were in the beginning! I made multiple slides, looking for features such as spore size and shape. I like to think my skills at making slides got better, but it was probably pure luck that I managed to get a beautiful slide of the cheilocystidia of my vexing Hebeloma species.

Gill tissue and spores of H. velutipes, stained with phenolphthalein. Photo by Sarah Ellis.

I also had the opportunity to extract DNA from two of my difficult specimens, including this one. After analysis there were some likely matches for the sequence, which helped give me a good idea of where the species fit. It was valuable process to learn and I am excited that future researchers will be able to access and build on this sequence data.

All in all, I collected over 30 mushrooms, selecting 15 to study in depth and include in the UBC Herbarium database. Interestingly, I identified several that do not seem to have been well-documented in B.C. yet, including the inconspicuous Psathyrella pseudogracilis found in my own backyard. I found quite a few poisonous or questionable species that are good to be aware of, because they resemble harmless mushrooms. I also collected some great edible species that look nothing like a typical “mushroom”, such as Hericium erinaceus.

Two large H. erinaceus, a “toothed fungus”. I found these on the side of a tree trunk by Nitobe gardens.. Photo by Sarah Ellis.

This project really opened my eyes to the incredible diversity of mushroom species, admittedly just a small portion of the kingdom of Fungi. Only about 5% of the estimated number of fungal species have been identified (Molina et al. 2001), so there is much still to uncover. Now each time I walk in the woods, I can’t help but watch for mushrooms. I am, however, a little more cautious about eating them!

Works Cited

Alvin, C. et al. 2010 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers ’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 28th Annual Report. Clinical Toxicology 49.1 (2011): 910–941. Web. 27 Dec. 2015.

Boa, Eric. Wild edible fungi: A global overview of their use and importance to people. FAO: Rome 2004.

Marley, Greg A. Chanterelle dreams, Amanita nightmares: The love, lore, and mystique of mushrooms. Chelsea Green Publishing: Vermont 2010.

Marciniak, Beata et al. “Poisoning With Selected Mushrooms With Neurotropic And Hallucinogenic Effect.” Medycyna Pracy 61.5 (2010): 583-595. MEDLINE with Full Text. Web. 24 Dec. 2015.

Molina, R. et al. “Addressing uncertainty: How to conserve and manage rare or little-known fungi”. Fungal Ecology 4.2 (2001): 134-146. Web. 27 Dec. 2015.