Mushroom collectors in their natural habitat, Manning Park. Photo by Catriona Leven.

At the beginning of September, I was lucky enough to be given the opportunity by Dr. Mary Berbee to undertake a Directed Studies project in her lab, assisting on the Edible and Poisonous Fungi Project. This project ultimately aims to create a database of mushrooms found in British Columbia, as well as a leaflet of the most common mushrooms – edible, poisonous, or unknown – that are being collected.

Why was I so excited to study fungi? Fungi were something I knew very little about, and the chance to find out more was enticing, and because they are such an unknown and mysterious group. Once considered plants, now known to be more closely related to animals than they are to plants, they are still the purview of botanists.

Over 90% of vascular plant form tight-knit mycorrhizal associations with fungi, where fungal hyphae and plants roots are inextricably interconnected to the benefit of both; the extensive, wide-reaching growths of fungal hyphae beneath the surface of forests have been shown to link distant plants together, allowing communication. Fungi are important decomposers, recycling nutrients from dead wood and other organic matter, and contributing essentially to biogeochemical cycles. Both wild and farmed mushrooms are economically important. And culturally, many places around the world have long and rich traditions of collecting mushrooms.

They are also odd, confusing, and hard to identify. Many of the species we find in British Columbia have been given both common and scientific names based upon experience from other parts of the world. Many of the scientific species names we apply across continents are probably being applied to fungi that are actually not the same species, even if they look similar. Determining species in fungi is tricky; most of their lives are spent as almost invisible mycelia below the soil, or in the wood of trees. Even when mushrooms are produced, appearance is not a good indicator of species, as mushrooms can be both varied within a species, and very similar or identical to distantly related mushrooms. Genetic studies are a good way to work out if specimens classed under the same name are the same, but even then it can be hard to tell. Determining sexual compatibility between fungi is difficult, as they have complex life-cycles, frequently don’t reproduce in the lab, only in natural conditions, and often do not conform to our human norms of life cycles and what we consider sex to be. Ustilago maydis, for example, has 50 different mating types, and cannot complete its lifecycle unless it successfully manages to complete sexual reproduction, which it will only do when growing on a plant.

This is the confusing and wonderful world that I encountered both in my talks with the many people who know far more about mushrooms than I, and in my perusal of mushroom identification books and primary scientific literature. Everyone is somewhat confused, but many people are working together to try and work things out. One of the things I found really lovely about becoming involved in the mycological community is how important non-scientists and amateurs are to the field, and the importance of academic and amateur cooperation.

: Standard Herbarium photograph, with colour checker and scale bar. This particular photo is of Hypholoma capnoides. Photo by Catriona Leven.

I am getting ahead of myself, however, for before I could tackle the confusion of mushroom identification, I first had to find some mushrooms. I began by joining the Vancouver Mycological Society on its annual foray to Manning Park. Everyone was unfailingly kind, enthusiastic, and helpful, and didn’t mind answering my many questions. Going out with people who are so passionate and experienced about mushrooms helped me to appreciate what an amazing and diverse fungal world there is out there, and how much there is to discover. Paul Kroeger, a venerable name in the mycological world, was particularly resplendent with anecdotes and interesting tidbits about mushrooms, as well as having an uncanny ability to identify them on sight. It was all a little overwhelming, with multiple names often being mentioned for the same mushroom, and people chiming in with their different experiences; at the end of the weekend the tables were replete with a bewildering array of specimens! I came away with five mushrooms to begin building my collection, and felt that I had at least started on my rapid learning curve in the field of mycology! The Manning Park foray taught me what notes were important to take, the importance of taking them as soon after collection as possible, and allowed me to first begin dipping my toe into the wealth of experience within the Vancouver Mycological Society.

Mushrooms galore and happy mushroom enthusiasts at Manning Park. Photo by Catriona Leven.

The ‘Fungus Among Us Festival’ was another great experience and useful collecting trip, with people from all walks of life and levels of mushroom knowledge coming together to walk through the woods, collect mushrooms, and then lay them out in an almost dizzying display upon tables in the Myrtle Philip School hall. After collections were made, mushroom experts frantically scribed little slips to identify specimens and where they had been collected, and often included little asides, like ‘smell me!’ on the Hygrophoropsis olida label; these mushrooms smell distinctly sweet, almost like marzipan. My other two collecting trips were around the UBC campus and in the Strathcona neighbourhood, where even in the midst of concrete and roads, I found fascinating mushrooms, and learned the importance of bringing together history, geography, biology and an understanding of your local surroundings in studying them.

Collecting a large enough quantity of mushrooms was never the main problem with this project – identifying them, now, there was the challenge! Whilst I have 15 mushrooms identified, I will not be too surprised if subsequent genetic work shows I was on the wrong track! I spent many hours in the lab, with a jar of slides and a razor blade for sectioning close to hand, staring down microscopes with some bemusement. I soon realised that my microscope skills were another thing that were going to be sorely tested. I like to think that they are at least slightly better than they were! I discovered that exciting things can happen when you put chemicals on mushrooms – Melzer’s solution, for example, can variously turn features blue, red, or almost black. I also learned the importance of spores, and the many varied shapes that they could take, from smooth and elliptical to round and very spiky, and just how unknown fungi are. Many of the books I was using for identification had been written about European species. It wasn’t long before I was getting very excited when I found recognisable microscopic characters, and my friends soon got used to me answering most questions of ‘Where are you?’ with ‘In the lab, poking away at my mushrooms!’.

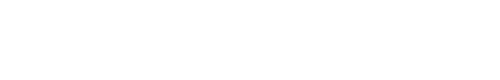

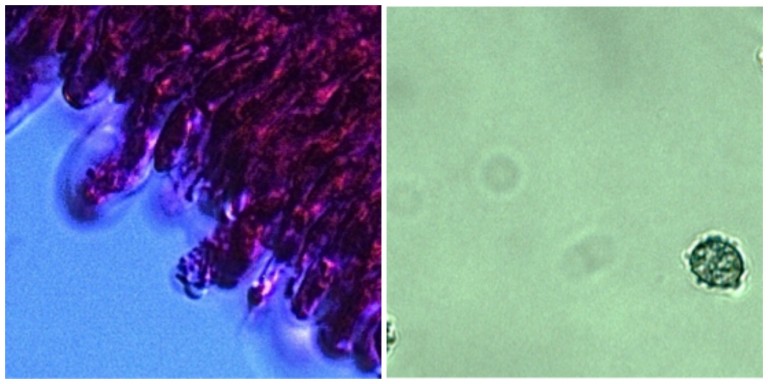

: Important morphological characteristics include basidia (left), the spore-bearing structures in Basidiomycetes, as seen here in a slide from Amanita muscaria stained pink with Phloxine, and spores (right) from Lactarius glyciosmus, with warts and ornamentation reacting blue in Melzer’s reagent. Photos by Catriona Leven.

My fifteen mushrooms will, ultimately, end up in the collections of the UBC Herbarium. I have entered my data into both the Edible and Poisonous Mushroom database being complied by Dr. Berbee, and Mushroom Observer, a website where anybody can note their mushroom observations and peruse what other people are finding. This project has been enjoyable, fascinating, and challenging; I have learned a huge amount. I would like to say thank you firstly to Dr. Berbee and her lab group, particularly Dr. Berbee herself and Ludovic Le Renard, whom I asked the most questions of; they were always willing to point me in the right direction. Secondly, thank you to the Vancouver Mycological Society and the Whistler Naturalists, whose members were friendly, helpful, and incredibly informative. Thirdly, thank you to UBC and particularly the UBC Herbarium, for providing both the opportunity and the facilities for the project.