Ever since I can recall I have loved frogs. Some of my first memories were of catching frogs in the swamps and ponds of Northwestern Ontario. I think I spent whole summers doing nothing but. I caught Northern Leopard Frogs, Wood Frogs, Gray Tree frogs, Spring Peepers, Mink Frogs, Green Frogs and American Toads – every frog to be found in those environs except the Boreal Chorus Frog but one day… Wherever I travel I’m always on the lookout for new species and frogs are on the top of my must see list. That’s probably why, when an email appeared in my inbox in February advertizing for a volunteer position with the Oregon Spotted Frog (OSF) Capture Mark Recapture (CMR) study, I leaped at the chance (pun intended). Up until then I wasn’t sure I would ever get to see this endangered frog in the wild. There are only about 300 breeding females left in Southwestern BC, the only place they are found in Canada, the likelihood of me stumbling across one while trudging through the wetlands of the Lower Mainland were pretty slim.

Oregon Spotted Frog, Rana pretiosa

Here was my chance to see the goofy-eyed Oregon Spotted Frog, Rana pretiosa, in its natural habitat. I contacted Kristina Robbins immediately. She is the BC Ministry of Forest Lands and Natural Resource Operations Ecosystems Biologist for the project. She was enthusiastic to have me join the project, but probably not quite as much as I was.

This capture, mark and recapture study, begun by SFU PhD Candidate Amanda Kissel, is used to help determine the population trends of the frogs. By utilizing the data over multiple years more accurate population estimates and annual survival rates of adult males and females are determined. From this information, age structure of the population, as well as rate of growth or decline is determined. This information is vital in conservation efforts for this endangered frog and I was going to be a part of it.

My part in the study was originally planned for two weeks starting late February, but the whims of nature forced us to get it done in only 6 days in March. Those frogs just didn’t want to breed in the snow for some reason.

Early in the morning of Monday March 10th Kristina and I headed out Agassiz to meet with the OSF team at the basement suite I would call home that week. I met Michelle Segal, the lead technician, and Hannah Gehrels, second in command, and the four of us headed out to the Morris Valley to begin my first day among the frogs. Once there we proceeded to check the traps – collapsible mesh minnow traps – 60 spread between three areas out in the wetland.

Morris Valley Traps

Frogs in the traps are bagged by trap number and brought back for processing. What is involved in “processing” a frog, you might ask? Well first a captured frog is scanned for a PIT tag. Passive Integrated Transponder tags are rice grain sized, glass-coated scannable devices that are placed under the skin of the frogs so they can be easily identified again. If a captured frog has a PIT tag we know it was a recapture either from earlier this season or a previous study season. After scanning and recording the PIT tag number (if found) each frog has its Snout Urostile Length measured. This is from nose to groin, which lines up with the “tail” bone or last vertebrae (urostyle) of the frog. The right shank length (analogous to your shin) and weight are also measured and recorded. Sex is determined and recorded along with notes on condition, such as gravid (filled with eggs), in amplexis (mating) and anything else of note. Those without PIT tags have one inserted through a small cut made in the skin on the back (don’t worry the frogs don’t seem to notice). All of this data is recorded in waterproof notebooks and entered for data analysis later.

Measuring Snout Urostyle Length (SUL)

It was still chilly that first morning and we didn’t end up catching many frogs in the traps. But the day did produce a first for me – I stumbled across a pair of OSF’s in amplexis – where the male frog latches onto the back of the female using his beefy forearms and nuptial pads on his thumbs. He holds on to her so he can fertilize the eggs she will lay.

Oregon Spotted Frogs are elusive wetland frogs that are not particularly easy to find. They bury themselves in mud and aquatic vegetation and disappear right before your eyes. I was not really expecting to come across many out in the open and since they are so well camouflaged spotting one can be tricky. My reaction to the mating pair was “Um there is a mating pair here. What do I do?” “CATCH THEM!!” was the reply. Hannah dashed over and caught this pair to be processed with the rest caught in the traps. Albeit without separating the pair – we don’t want to disturb a naturally mating pair too much. This was the highlight for me, both since it provided extra data for the study and now I could officially put the Oregon Spotted Frog on my list. I would not feel comfortable putting frogs trapped on my official list. Throughout the course of my time with the project I saw many more Oregon Spotted Frogs in their natural habitat but that pair would always be the first.

The elusive Oregon Spotted Frog – can you see the mating pair?

Trapping and processing of this sort continued for the next five days, but the biggest surprise came on my second to last day. The Maria Slough (the second breeding site) frogs decided to breed earlier than usual, just at the peak time of the Morris site frogs. An “all hands on deck” call went out to the OSF community and three extra crew members came out to help deal with this plethora of frogs. On our peak day we caught 94 frogs at Maria, and 36 frogs at Morris. The totals for my time with the project were:

Morris:Total Frogs: 151, Recaps: 73, New: 77

Maria: Total Frogs: 143, Recaps: 50, New: 93

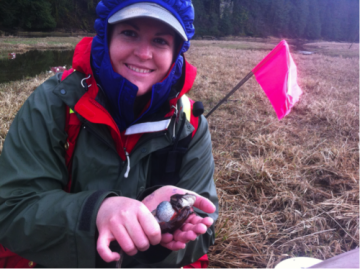

We also managed to catch the largest female of the study – over 100mm long.

Largest female caught in the study (my hands are quite large)

I hand-captured (not in the traps) a total of eleven frogs over the course of 6 days, of course several of these were mating pairs, which increases the numbers and reduces the difficulty in capture. They were not all Oregon Spotted Frogs, there were also quite a few Northern Red-legged Frogs.

Through the course of the trapping we saw some interesting mating behaviours. The unnatural proximity within the traps causes the frogs to do some strange things. There were several tiny males that really had no business mating with massive females. The size difference could be astonishing. Those tiny male arms could barely get around the female. There were also some multiple pairings of two males on a single female in various positions and also between different species in pretty much any combination you could think of. There was just a lot of confusion in the constrained space of those traps.

My time with the Oregon Spotted Frog team was truly a great experience and I hope that the data I helped add to the project will help these endangered frogs in the future. I want to thank the OSF team – Kristina Robbins, Michelle Segal and Hanah Gerhels, as well as the BC Conservation Foundation for making my participation in this project possible and a real blast.

Top to bottom – Male OSF, Female OSF Male Northern Red-legged Frog

For more information on the Oregon Spotted Frog please check out these resources:

Oregon Spotted Frog BC Recovery Strategy

Species at Risk Public Registry

BC Frog Watch Program Factsheet

BC Species and Ecosystems Explorer

The author holding a Northern Red-legged Frog (Rana aurora)

Photos: personal photos by Chris Stinson.