As the Cowan Tetrapod Collection Curator and the Beaty Biodiversity Museum’s bird specialist, I’m part of the team caring for the globally diverse specimens housed at the Beaty Biodiversity Museum. For me, the avian specimens are not just stuffed birds whose lives have been extended for another 300 years. When I go through the cabinets pulling out sets of birds for visiting researchers or for students, a rush of memories comes unbidden. These cabinets are my photo albums. Inside my mind, a carousel slide projector starts flashing images every time I encounter a bird I know. Each slide is a different day. Was it stinking hot with sweat dripping down my back when I first saw this bird? What was it doing? Who was I with? Had we walked a great distance? Were we having lunch? Was I on a boat tasting salt under the noonday sun, or was it so dark beneath the tropical forest canopy that all light was extinguished beyond ten meters in front of us? Did we hear the bird and never find it?

The other day, I was in the falcon cabinet. My eyes feasted on the beauty of all the falcons but my heart leaped with happiness on seeing the Aplomado.

Falconidae, the Falco clan of birds has many fringe members that diverge from the lofty swift ones. Swallow-sized falconets hunt in packs catching large butterflies and grasshoppers. Crane-like Secretary Birds stride in tall grass stomping snakes to death. Chimango caracaras swarm like rats over South American garbage dumps scavenging for food reminiscent of raucously gulls circling and blanketing our local landfills. But my favourite falcons are the aristocrats, the russet-hued trio of immaculately dressed falcons sporting scallop-patterned black waistcoats.

“Aplomado Falcon at a Falconry Center” is the title of this photograph by Peter K Burian – commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aplomado_Falcon_at_a_falconry_center.jpg – This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en

Long-tailed and sleek Aplomado Falcons are the only waist-coated falcons near in size to the mighty Peregrine. In build, Aplomados are lanky basketball players compared to their quarterback cousins. They grace the skies along the Rio Grande River as it winds its way through Arizona and Texas and their range extends far to the south to the Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego on the tip of Cape Horn. I have seen them at both extremes of their range and numerous countries in between. On Old Isabel Road near South Padres Island, Texas, the hacking platforms used to reintroduce this formerly US extirpated falcon are still standing. They are a reminder of how easily a shotgun can result in a species disappearance.

Whenever I see an Aplomado Falcon, my mind drifts to that incredibly windy day Esteban Daniels and I spent on an estancia near Ushuaia. A hillside town clinging on the coast overlooking the Drake Passage, that formidable storm-tossed waterway that must be crossed to reach the Antarctica Palmer Peninsula. I remember the car rocking in the wind as we ate our lunch watching undulating wave patterns form and reform in the tall grass on the island’s interior plateau. A herd of 100 horses had come and gone over the low rolling fields. The birding had been excellent and all the Patagonian specialties we had been questing for had been seen. We were content. Glad to be out of the wind sating our hunger while munching on our sandwiches. We were totally stunned when a white mystery bird glided onto a fencepost that was perfectly framed by the car’s windshield. Albino birds are so confusing. Our brains, so accustomed to navigating technicolour details, are instantly forced to delve deeper to identify a bird by shape and posture alone.

Watch the video and share our minute of bewitchment!

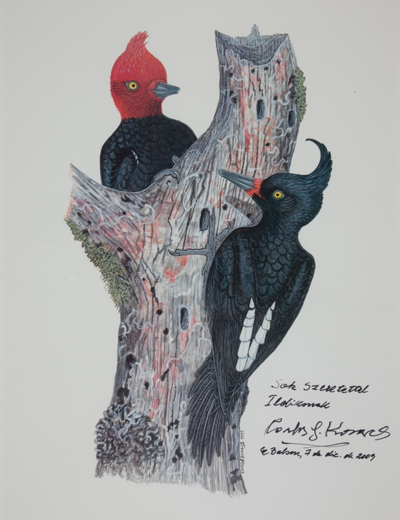

Holding the museum’s Aplomado in my hand not only recalls that day in Tierra del Fuego but also another a few years earlier. The day I meet the Kovacs brothers and one of their sons at their family museum in El Bolsón; a beautiful Western Argentinian town nestled in the Andean foothills. This falcon I am holding was skinned and stuffed by their father. In a perfect world equipped with time machines, I would travel back and plead with this master preparator to be my mentor. Kovacs’ skins are in a league of their own. I so want to learn the subtle tricks he uses to make them so feather-perfect. I have opened the museum cabinets looking for this specimen needing to photograph its label for the webpage about their father now posted on the BBM’s Contributor webpage.

Holding this bird crafted by him causes my mind to soar as this bird did in real life. I love remembering the haunting beauty of all the places I have had the good fortune to witness this species in action. Snippets of conversation and laughter glide in and out of my internal soundscape of the meal shared and hours spent looking at, and handling, the birds in the collection of this remarkable family who are custodians of such a wealth of Patagonian bird lore.

I’m afraid that I was a disappointment. Given that my name is Szabo, the Kovacs assumed that I, like them, spoke Hungarian. They gifted me with this print and challenged me to learn just enough of my fraternal heritage to read it.

Magellanic Woodpecker are in the New World genus Campephilus. Ivory-billed Woodpeckers (now extinct) were the most northerly representative of this genus. This print is signed by the artist. (Print photographed by Quinn McCallum)

This summer and fall, the ‘What Am I?’ window located in the Tetrapod section of the Beaty Biodiversity Museum features the Kovacs. Come to the Museum and test your skills at identifying the bird on display and on the cover of their book The Illustrated Handbook of the Birds of Patagonia.

Falco rufigularis Bat Falcon by Joao Quental – commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:OFalco_rufigularis_Bat_Falcon.jpg licensed under the terms of the cc-by-2.0 – https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en